604 465 4322

604 465 4322General Store Site 12294 Harris Road Pitt Meadows, B.C.

Click Here for Directions& Visiting Hours

Smallpox

Smallpox

Smallpox is a highly contagious disease caused by a viral infection. There are two strains called variola major and variola minor. The symptoms of variola major are fever, lethargy, headache, body aches, sore throat, vomiting and rashes made up of fluid pustules that join together leading to scabs which will come off, but will leave scarring and can result in deformities. In addition, smallpox can cause death. Variola minor infection causes fewer systemic symptoms such as a less extensive rash, less scarring, and fewer fatalities. Smallpox is historically one of the deadliest diseases, but it is also the only human disease to have been eradicated by vaccination.

Origin

The origin of smallpox is unknown. Smallpox-like rashes were found on Egyptian mummies from the 3rd century BCE. The finding of smallpox-like rashes on Egyptian mummies suggests that smallpox has existed for at least 3,000 years. The earliest written description of a disease like smallpox appeared in China in the 4th century CE (Common Era). The disease historically occurred in outbreaks.

Vulnerable populations

Vulnerable populations are pregnant women and people who are immunocompromised. The highest smallpox infection rates were in persons 0–19 years of age, but the highest death rates were in those 45 years of age. Death occurs in about 30% of infected people, typically in the second week of infection. It is estimated that there were more than 300 million deaths caused by smallpox worldwide in the 20th century.

Symptoms

It takes 1 to 3 weeks after exposure to the virus for the illness to take effect. The duration of the illness is 4 weeks. Symptoms of a typical smallpox infection begin with a fever and lethargy for about two weeks after exposure to the virus. Smallpox can cause a severe rash over the whole body. The rash looks like red bumps that gradually fill with a milky fluid. The fluid-filled bumps are all in the same stage at the same time. Fluid-filled pustules would develop and expand, in some cases joining together and covering large areas of skin. In a few days, a raised rash appears on the face and body. Sores form on the inside of the mouth, throat, and nose. In about the third week of illness, scabs are formed and separate from the skin. Most survivors had some degree of permanent scarring, which could be extensive. Other deformities could result, such as loss of lip, nose, and ear tissue. Blindness could occur as a result of corneal scarring. Other symptoms are severe headache, body aches, sore throat, and vomiting. Variola minor was less severe and caused fewer of those infected to die.

Transmission

The disease occurs only among humans and is passed from person to person. Smallpox is an airborne disease that spreads fast from inhalation of droplet nuclei expelled through the back of the throat of an infected person. The coughing, sneezing, or direct contact with any bodily fluids could spread the smallpox virus. Smallpox was also spread by close contact with the sores of an infected person. A patient remained infectious until the last scab separated from the skin.

Smallpox originally came to Canada by European traders and settlers. In modern times smallpox was brought in by passengers by modes of transportation such as boat, train, and aircraft. Some Canadians infected with smallpox got the disease after leaving countries in Africa and Asia. Hospital staff that encountered the infected also came down with the disease.

Smallpox Variolation in Canada

Variolation is the act of inserting viral matter or pus from a lesion found in a smallpox patient by putting it inside a small scratch in a person’s arm who did not already have smallpox so that a mild infection would result, and this would lead to protection from a more severe version of the virus in the future. Variolation was first used in British-held Quebec in 1765. By 1769 immunization among the prominent English and French families in Quebec and most of the British troops stationed in the colony had been implemented. Variolation also benefited the Indigenous population of British North America. In 1796, British colonial authorities allowed the Mohawk living near Kingston area of Upper Canada (an historical name for modern-day Ontario) to be variolated. Smallpox immunization through variolation would continue in British North America until the 1850s.

The First Vaccine

Dr. Edward Jenner discovered the first vaccine in 1796. This vaccine was made from cowpox matter. Cowpox is a disease of cows that when transmitted to healthy humans causes sores, fever, vomiting, fatigue, and sore throat. Dr. Jenner cut an incision in his gardener’s son and put matter from a cowpox sore inside. He believed that this would lead to immunity of cowpox. After the boy recovered from cowpox, Jenner inoculated the boy with smallpox matter to see if immunity to cowpox would also create immunity to smallpox. Jenner was right and the boy became immune to smallpox. Jenner’s work led to the widespread production and use of the smallpox vaccine. The modern smallpox vaccine is made from a weakened or killed form of a microbe, toxins, or a surface protein that is derived from a calf lymph. This vaccine does not contain the smallpox virus.

The Beginning of Vaccination in Canada

After Edward Jenner’s discovery, vaccination was used in North America. The first indigenous people were vaccinated in 1803 after travelling hundreds of kilometres to receive it. In 1807, Jenner sent a supply of smallpox vaccine to the Five Nations of the Iroquois along with his book about vaccination to help explain how it worked. The chief of the Five Nations received the gift with great appreciation and wrote back to thank Jenner, saying “we send with this a belt and string of Wampum in token of our acceptance of your precious gift, and we beseech the Great Spirit to take care of you in this world and in the land of spirits.” Smallpox vaccination saved many Indigenous Canadians, but it would take time for its benefits to be appear consistently everywhere in Canada because smallpox continued to come from travellers from the United States, where vaccination was adopted more slowly. Moreover, obtaining enough vaccines was challenging.

The Hudson Bay Company and Vaccination

Before a strong localised government, businesses like the Hudson Bay Company assisted in the transportation of knowledge and medicine. Dr. William Todd, a surgeon and an HBC employee near the border of modern-day Manitoba and Saskatchewan heard of “some bad disease” infecting locals. Todd, who had recently received a fresh supply of vaccine from England, guessed correctly that the disease was smallpox. He immediately vaccinated sixty First Nations living in the vicinity of Fort Pelly, and he also taught them the technique of arm-to-arm vaccination, so that they could vaccinate others. In arm-to-arm vaccination, as soon as a cowpox pustule appeared on a vaccinated person’s arm, material from the lesion was removed and used to vaccinate another person. Todd also sent fresh vaccine to other HBC traders, resulting in the company being able to reduce the spread.

Over the next two years, HBC launched a massive vaccination program with the goal of inoculating every person within its domain. Due to the HBC’s efficient transportation systems and organizational structure, the Hudson’s Bay Company served like a public health agency across Western Canada during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Their efforts would limit smallpox and its death toll for several decades.

Duration of Immunity

It is unclear how long the smallpox vaccine provides effective immunity, but it is unlikely to be more than 10 years. An interesting observation during the smallpox infection was that people who survived natural smallpox developed life-long immunity against the disease, but immunity following vaccination begins to wane in vaccine recipients 3-5 years after they are vaccinated, but the majority of vaccine recipients retain some level of antibody up to 75 years after vaccination.

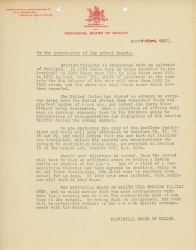

Active measures against the spread of smallpox in Canada

The decline of smallpox cases in Canada was due to vaccination, quarantine procedures at ports of entry, and less smallpox cases in other countries in which people travel to Canada. Canada followed International Sanitary Regulations of the World Health Organization. Every person entering Canada from abroad with the exception of a few countries presented valid evidence of vaccination against smallpox within the previous three years, or evidence of having had the disease in the same period. When there was a few people who had been advised to not take the vaccine they were placed under surveillance for a two-week period after arrival. In the four-year period 1959-1962, over a million people that entered Canada each year were required to present evidence of smallpox vaccination. Over 99% of this group presented such evidence or were vaccinated when they entered the country.

Canada’s vaccination programs were primarily directed toward newborns and children. Some programs started at the first year of school. Re-vaccinations were frequently carried out every five years at school. From 1952-1961, approximately 12 million doses of smallpox vaccine were distributed by Canadian manufacturers for use in Canada. Immunization programs were stopped in Canada in 1972 for infants, in 1977 for health care workers and in 1988 for Canadian Forces.

Enforced school vaccinations saved students from getting the disease, while younger children who did not attend school yet were susceptible to getting the illness. Siblings in the same family had different experiences because of prior vaccination.

The End of Smallpox

The vaccine helps the body develop immunity to smallpox. It was successfully used to eradicate smallpox from the human population. The last known smallpox case occurred in Somalia in 1977. In 1980, the World Health Organization declared that smallpox had been eradicated. Currently, there is no evidence of naturally occurring smallpox transmission anywhere in the world. As a result, the public does not need protection from the disease.

To return to the other diseases click here.

Smallpox Information for schools

Smallpox Information for schools

Smallpox Information for schools

Smallpox Information for schools

Smallpox Information for schools

Smallpox Information for schools